The Energy & Geoscience Institute announces Dr. Kristie McLin as Director of Research and Science and new Principal Investigator of the Utah FORGE project, succeeding Dr. Joseph Moore.

Other Resources

Fun with Geothermal

Categories

Feb 17, 2026

The Energy & Geoscience Institute announces Dr. Kristie McLin as Director of Research and Science and new Principal Investigator of the Utah FORGE project, succeeding Dr. Joseph Moore.

Jan 22, 2026

Kenya may not be the first country that comes to mind when thinking about geothermal energy, but it leads the world in geothermal electricity production per capita. Sitting atop the geologically active East African Rift System, Kenya has tapped into the Earth’s heat for power, agriculture, industry, and community development—transforming a once-overlooked resource into a cornerstone of its energy future.

Oct 16, 2025

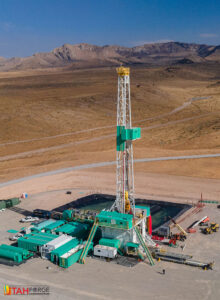

The heat beneath our feet flows through the earth in a complex pattern. Utah FORGE is situated in a heat reservoir that has been studied since the 1970s. In this webinar, Dr. Stuart Simmons delves into the unique geologic and geothermal resources found at Utah FORGE and the surrounding area.

The page you were looking for must have fallen into a well.

Home

Contact